The Secret Life of an Initial Access Broker

Victoria Kivilevich, Threat Intelligence Analyst and Raveed Laeb, Product Manager

Bottom Line Up Front

- Recently, ZDNet exclusively reported a leak posted on a cybercrime community containing details and credentials of over 900 enterprise Secure Pulse servers exploited by threat actors

- Since this leak represents an ever-growing ransomware risk, KELA delved into both the leak’s content and the actors who were involved in its inception and circulation

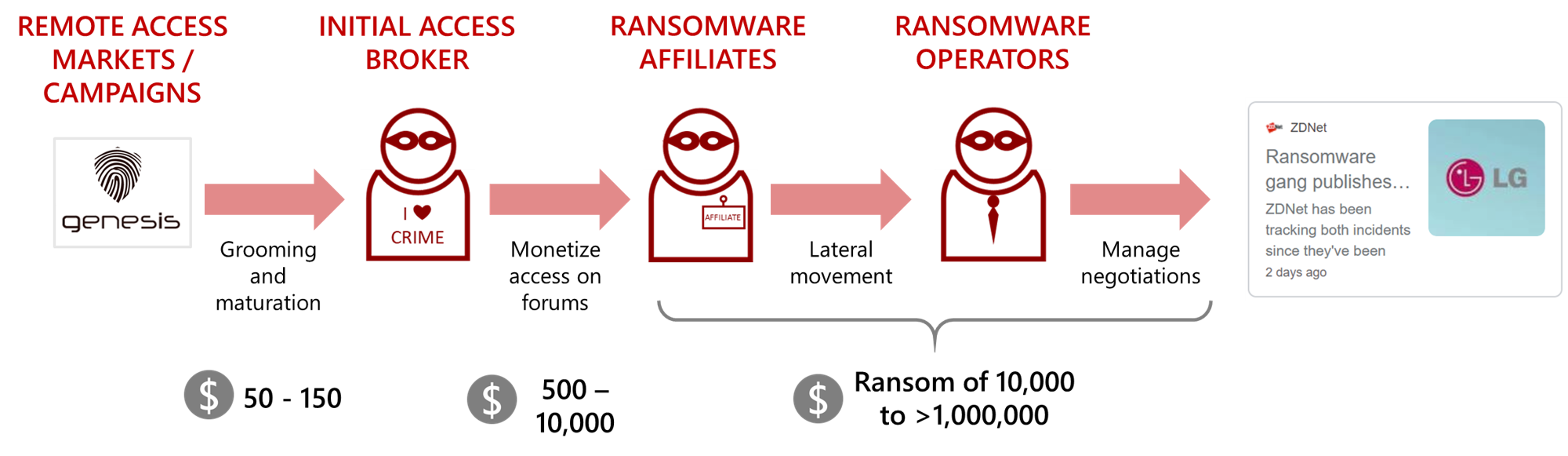

- This short research targets a specific tier of cybercriminal actors – Initial Access Brokers. These are mid-tier actors who specialize in obtaining initial network access from a variety of sources, curating and grooming it into a wider network compromise – and then selling them off to ransomware affiliates

- With the affiliate ransomware network becoming more and more popular and affecting huge enterprises as well as smaller ones, initial access brokers are rapidly becoming an important part of the affiliate ransomware supply chain

- The list leak mentioned above seems to have been circulating between several initial access brokers in cybercrime forums, and have been exposed by a LockBit affiliate who regarded the actors as unprofessional

- This event showcases the breadth of information that’s exchanged on cybercrime communities and, in KELA’s eyes, emphasizes the need for scalable and targeted monitoring of underground communities

RaaS Ecosystem 101

For the past year or so, the threat intelligence community has been closely tracking the ongoing changes to the ransomware landscape – noting the shift in business models and TTPs employed by ransom actors. While vendors may choose different terms – “human-operated”, “multi-stage”, “targeted” and more – they all carry the same meaning: ransomware actors are opting to go for targets that have more means and more incentive for payment, so they can demand higher ransom amounts.

One major aspect of this trend, commonly mentioned in the media for its inherent flare and optics, is the naming-and-shaming leveraging tactics used to further push ransomware victims to pay.

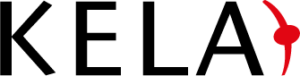

Another aspect is the cooperation between actors facilitated by the rise of targeted ransomware: in order to support work in scale, ransomware operators turn to partners and affiliates to fulfill their remote access needs. This cooperation results in two distinct stakeholders in the targeted ransomware-as-a-service supply chain: the ransomware developers who supply the infrastructure, and the partners who supply the network intrusion opportunities and deployment of the ransomware itself.

The affiliate model employed by GandCrab in 2019. Source: McAfee

Generally speaking, the affiliates working directly with ransomware operators are highly vetted, professional actors. At any given moment, most ransomware developers are recruiting only a handful of affiliates – essentially creating a pyramid-like hierarchy; some RaaS developers are very keen on their affiliates’ KPIs, with underperforming affiliates being removed from the program.

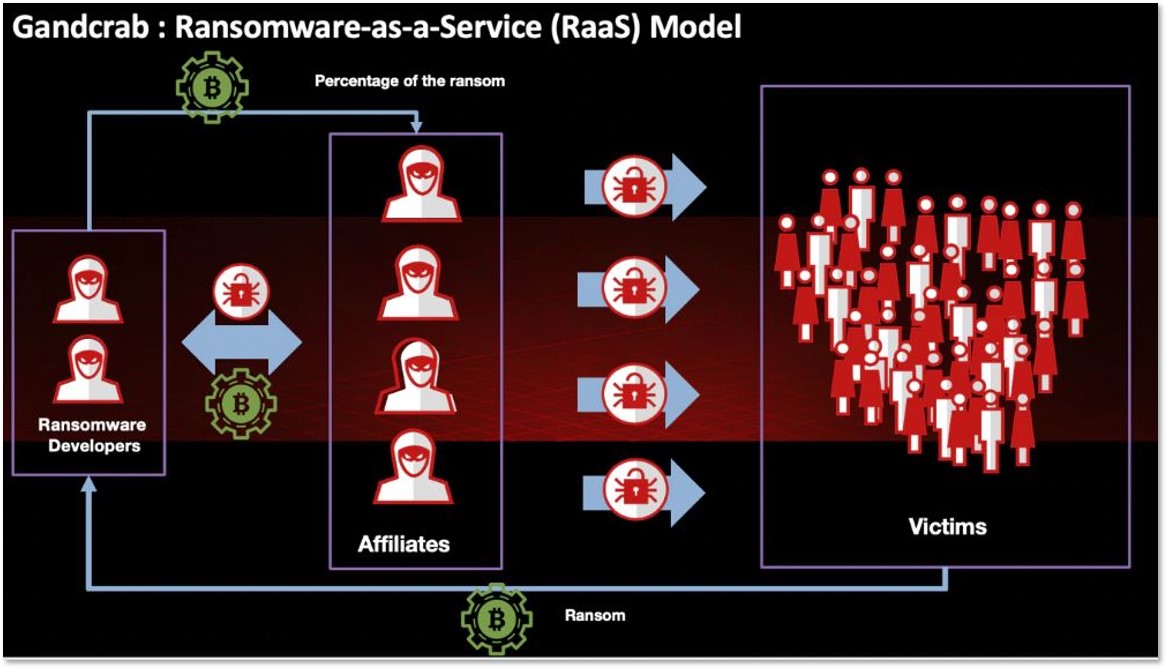

Post from a cybercrime forum (accessible and translatable through DARKBEAST) where a NetWalker ransomware recruitment ad shows a very specific criteria for affiliates

Essentially, affiliates may be perceived as mid-level management. Facing constant scrutiny from the developers and commission-based salary that’s dependent on successful network intrusions, the affiliates’ needs to constantly gain more network access gave rise to another actor type: the initial access broker.

Initial Access Brokers

Initial access brokers are generally lower-tier, opportunistic actors supplying the affiliates with access-as-a-service: they obtain initial access to organizations and then offer it for sale on the same underground forums occupied by RaaS affiliates. Affiliates then buy these initial accesses, pivot and move laterally until enough control is obtained so the ransomware can be spread and computers be locked.

Brokers and affiliates are not necessarily differentiated by their level of skill or expertise, but rather by the monetization channels they choose to employ. While affiliates or ransomware actors monetize networks by locking them and demanding ransom, initial access brokers are use-case agnostic: they sell network access to any actor – financially-motivated APTs (such as FINx groups), ransomware actors, data brokers, nation state actors trawling the cybercrime underground for leads or essentially any threat actor that has a way to monetize said access.

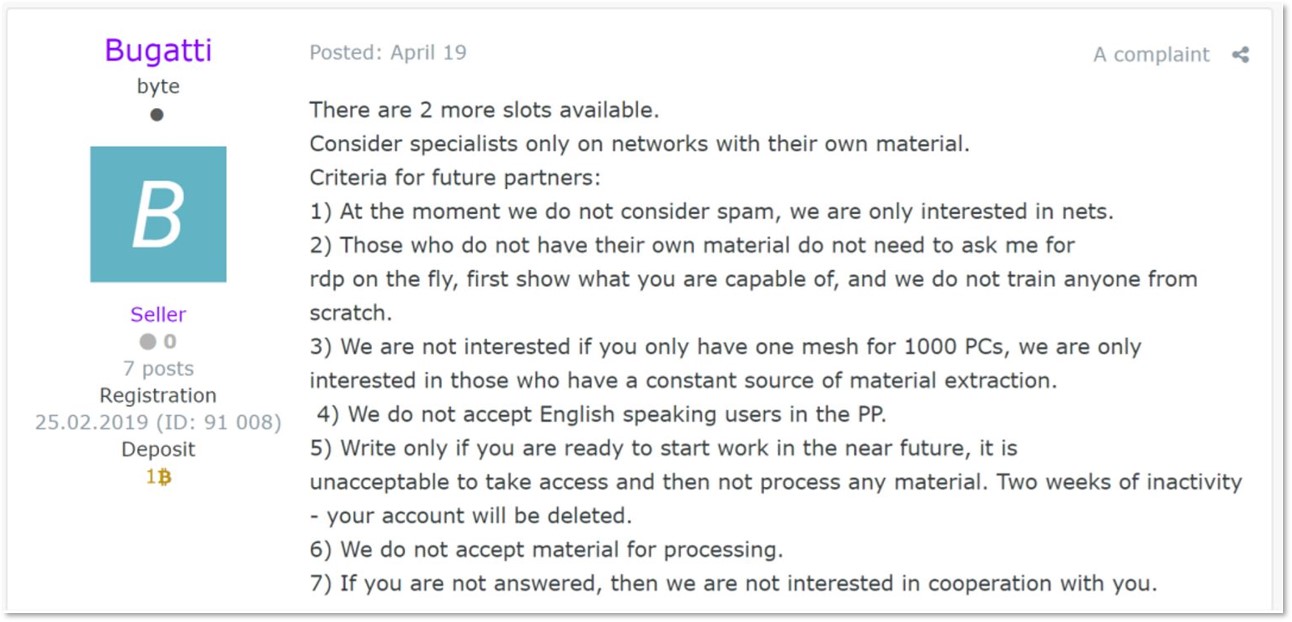

A handle used by an actor associated with the access broker collective known as FXMSP, offering network access to multiple organizations on the now-defunct KickAss Forum

Monetizing network access in the cybercrime financial ecosystem is nothing new, and initial access brokers existed long before the rise of targeted ransomware. However, they tended to have less clients. Monetizing network access can be hard, since fraud actors – who make up the lion’s share of active actors on most communities – are more interested in credentials that can be easily converted to cash in hand, whereas sophisticated actors who can monetize access to an obscure network were not, up until lately, in abundance. The recently-established RaaS programs have simplified the process and provided easy monetization channels for network access. These programs have enabled the entire chain of actors to increase profits, as high demand for network access (by affiliates) creates a higher supply of brokers dedicated to gaining network access.

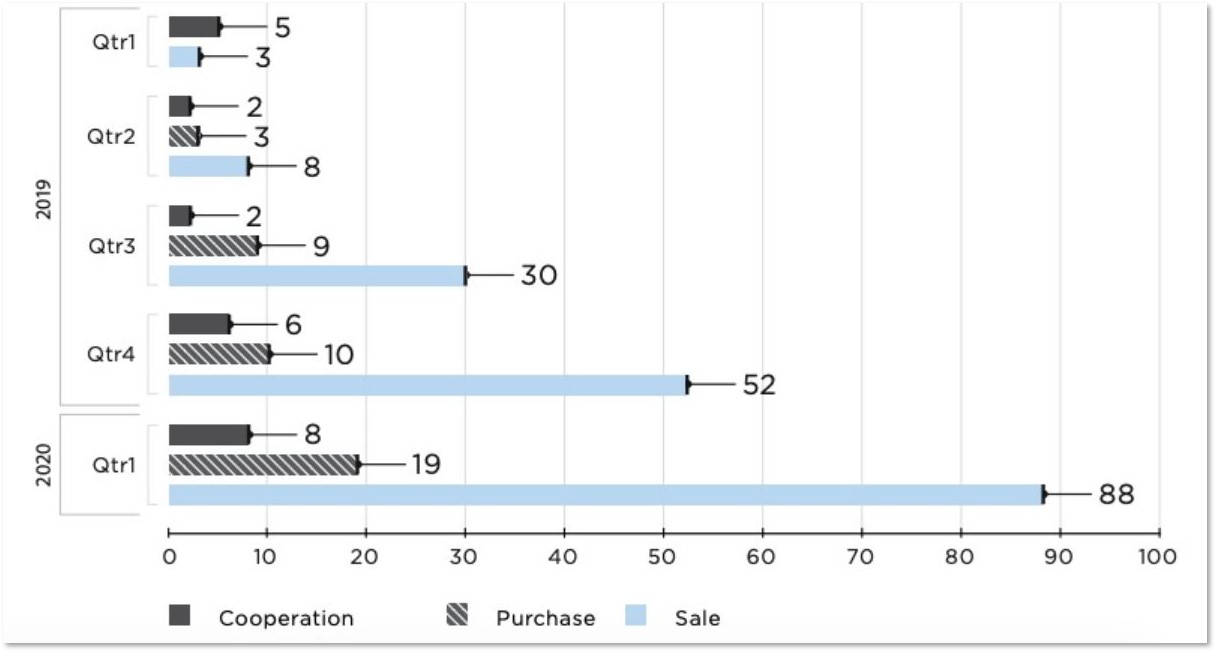

In 2019, due the rising tide of RaaS operators, threat intelligence research efforts started shifting towards access brokers as well. One of the notable actors to attract major attention was the loose collective known as FXMSP, which operated across multiple handles and communities. Others, such as “bc.monster” or “sheriff”, are currently becoming increasingly active across Russian-speaking communities. Initial access brokers are, in fact, becoming exponentially more prevalent in cybercrime communities; the amount of posts and offers dedicated to monetizing network access has risen drastically in 2020.

Remote access offering on cybercrime forums over time. Source: Positive Technologies

The Value Proposition of Access Brokers

Key enabling factors for the prevalence of access brokers (and, indirectly, to the rapid rise in targeted ransomware) are the automation and servitization of cybercrime.

Let’s take Remote Desktop Protocol – a key vector in targeted ransomware. A few years ago, threat actors needed to employ a wide variety of tools to get access to a valuable, functioning RDP server belonging to a corporation – including much time spent on reconnaissance, brute forcing and nitpicking victims.

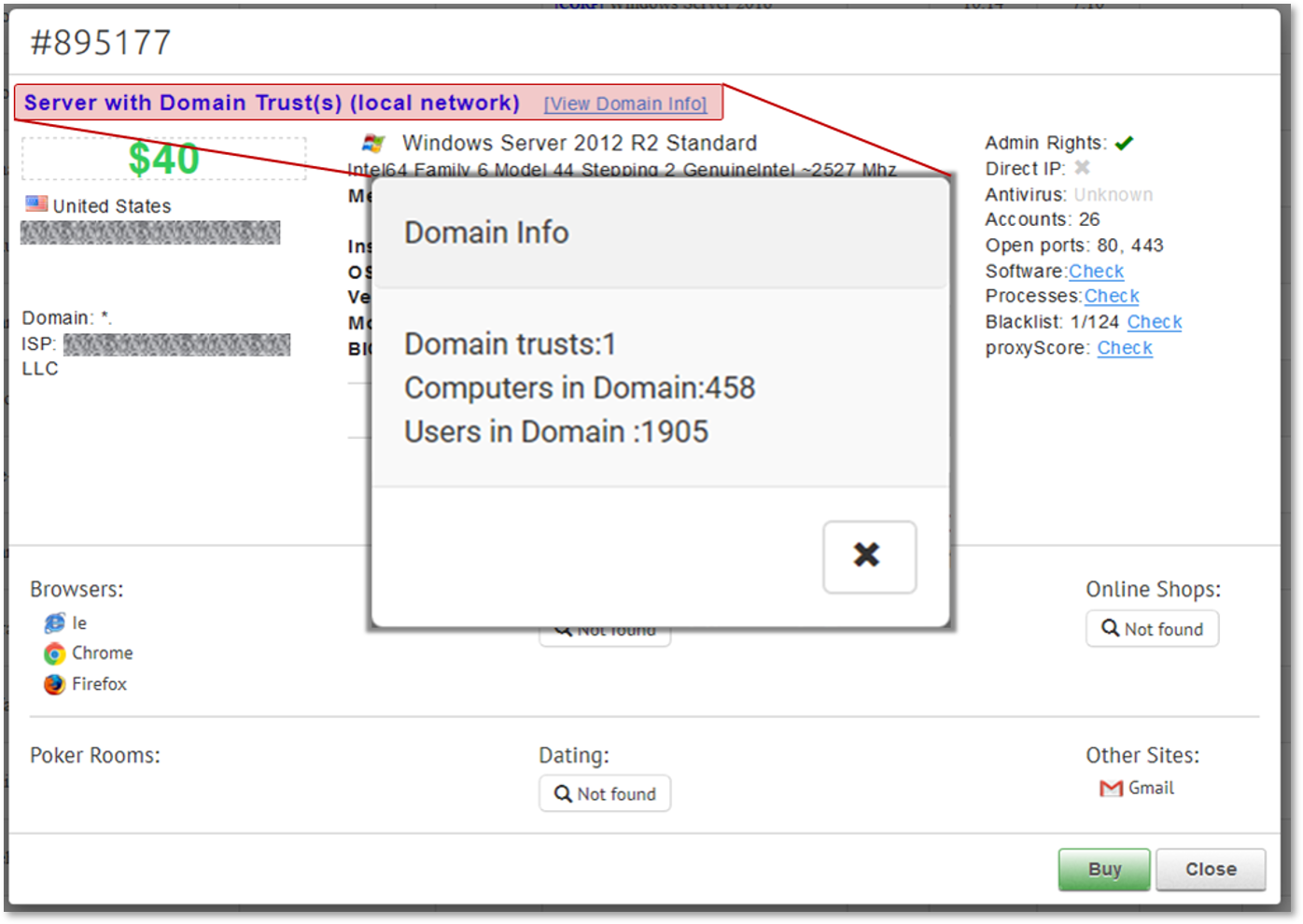

Today, one only needs to obtain an invite to one of the many Remote Access Markets and browse the continuously-updated selection of compromised machines offered for sale. One of the major RDP markets has lately also added a “CORP” flag – servers that are part of a corporate network are marked (and priced) differently, so actors can easily spot them and get the most bang for their RDP buck.

An RDP server belonging to an organization offered for sale on an automated market for USD 40

This wide selection of goods allows actors a higher volume of work. For a few hundred dollars, initial access brokers can acquire multiple RDP corporate servers; from that selection they can “groom” the ones that look interesting – perform some reconnaissance, escalate privileges or install further tooling. Once a target is ripe and ready, it can be offered for thousands of dollars on cybercrime markets where ransomware affiliates can acquire it and move forward with the final attack.

This model creates different stakeholders in the supply chain – each with their own expertise, scale of operations and profit margins. During each step of the process both the scope and price of the access get bigger – yielding profits to each stakeholder, and creating small, self-contained ecosystems that can support large-scale cybercrime efforts.

The Secret Life of an Initial Access Broker

On August 4, 2020, ZDNet, in collaboration with KELA’s tools, exclusively reported on a threat actor exposing a list of over 900 compromised Secure Pulse VPN servers – including credentials, session keys and other sensitive information being exposed. This was an interesting event for several reasons. First and foremost, the actual leakage provided visibility into targeted servers being used as potential ransomware targets – which has great intelligence monitoring value. Second, the leak – and the story behind it – provides an interesting behind-the-scenes look into the activity on an initial access broker.

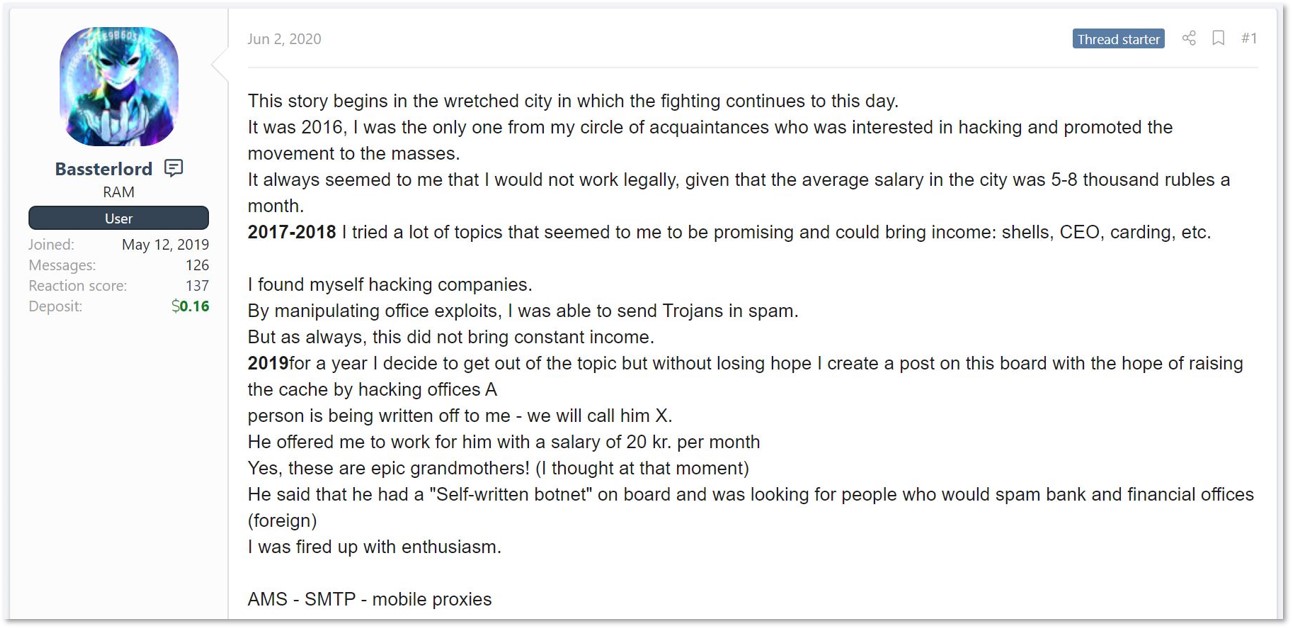

First, in order to understand the story behind the recent leak, one needs to get familiar with the threat actors involved. The first – a man from Ukraine who, according to his posts, started his hacking activities in 2016 – goes by the handle “Bassterlord”. According to the actor’s own accounts, after launching spam campaigns designed to deliver trojans and infostealers, he switched to targeting organizations under the mentorship of an unknown threat actor who hired him in 2019 and provided counselling.

In a competition of hacking-related articles held on a Russian-speaking underground forum, Bassterlord shared a writeup of his original story, of how his mentor offered him around $300 a month to send spam emails containing malicious attachments to banking and financial organizations. The actors have targeted 12,000 companies over almost one year, though they managed to infect only two of them. “Nothing worked for me, I was desperate,” shared Bassterlord in this write-up. This was when his mentor taught him how to compromise organizations via RDP. At the same time, Bassterlord claims that his mentor “got access to Sodinokibi” – probably referring to the mentor becoming a Sodinokibi affiliate, showcasing the typical relationship between an affiliate and a soon-to-be initial access broker. Eager to get more money, Bassterlord switched to another TTP.

Bassterlord’s current primary TTP involves the use of an automated script weaponizing CVE-2019-11510, an arbitrary file read vulnerability affecting Pulse Connect Secure SSL VPN, which has lately become popular with ransomware actors. Moreover, he states that he continues to work with his mentor and former employer, which is apparently still involved in Sodinokibi operations.

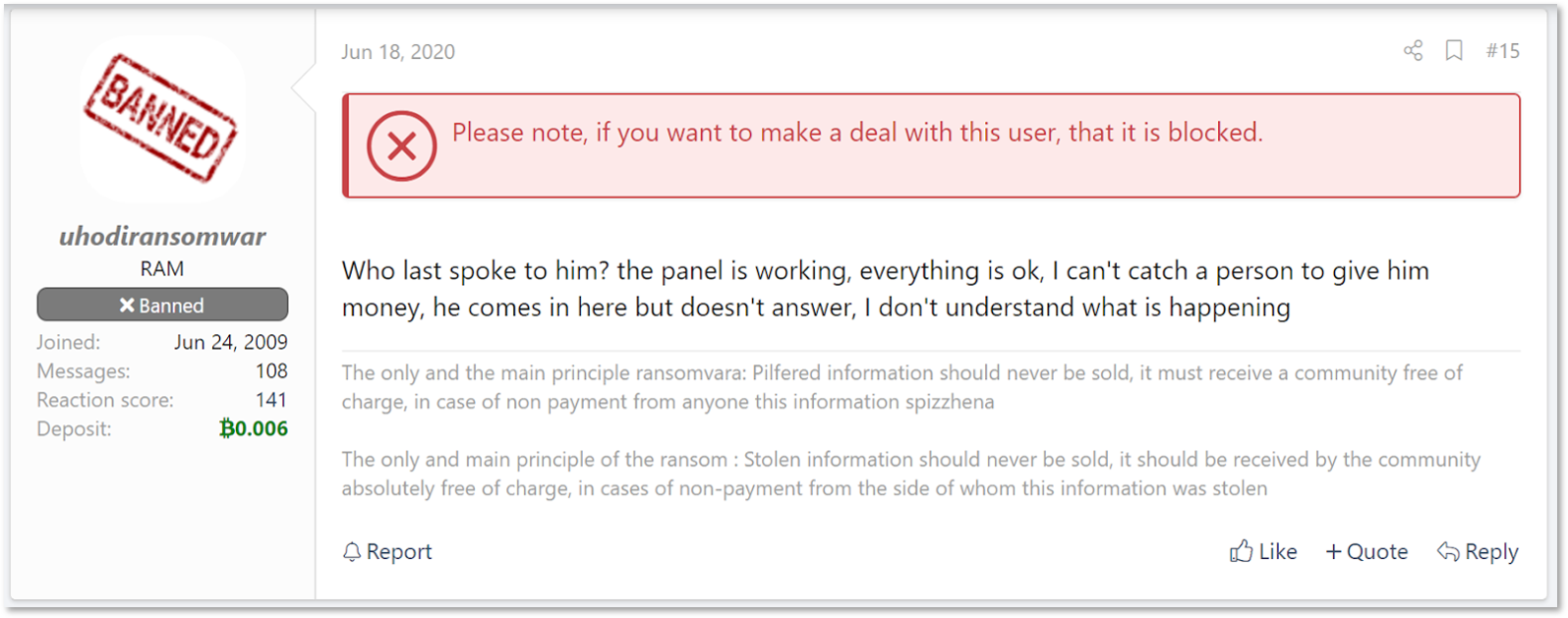

Another threat actor involved in the story is named “uhodiransomwar” (from Russian – “Go away, ransomware”), previously known as “m1x”. He is a veteran actor, active since 2009 (though freshly banned) on the same underground forum as Bassterlord. A major part of uhodiransomwar’s latest activity is small-scale ransomware: he mostly shares data from organizations he claimed to breach once no payment is received. It seems that he sometimes acts independently, and is also self-associated with known RaaS actors – such as LockBit.

A comment in the official LockBit affiliate recruitment thread by uhodiransomwar, claiming to have access to the affiliates panel

In the last few weeks, Bassterlord and uhodiransomwar have been publicly clashing in the forum – showing the contrasting views of a novice initial access broker and a ransomware affiliate, respectively. These ongoing clashes have led to the credentials leak mentioned above.

Setting the Stage: a Not-So-Great Initial Access Broker

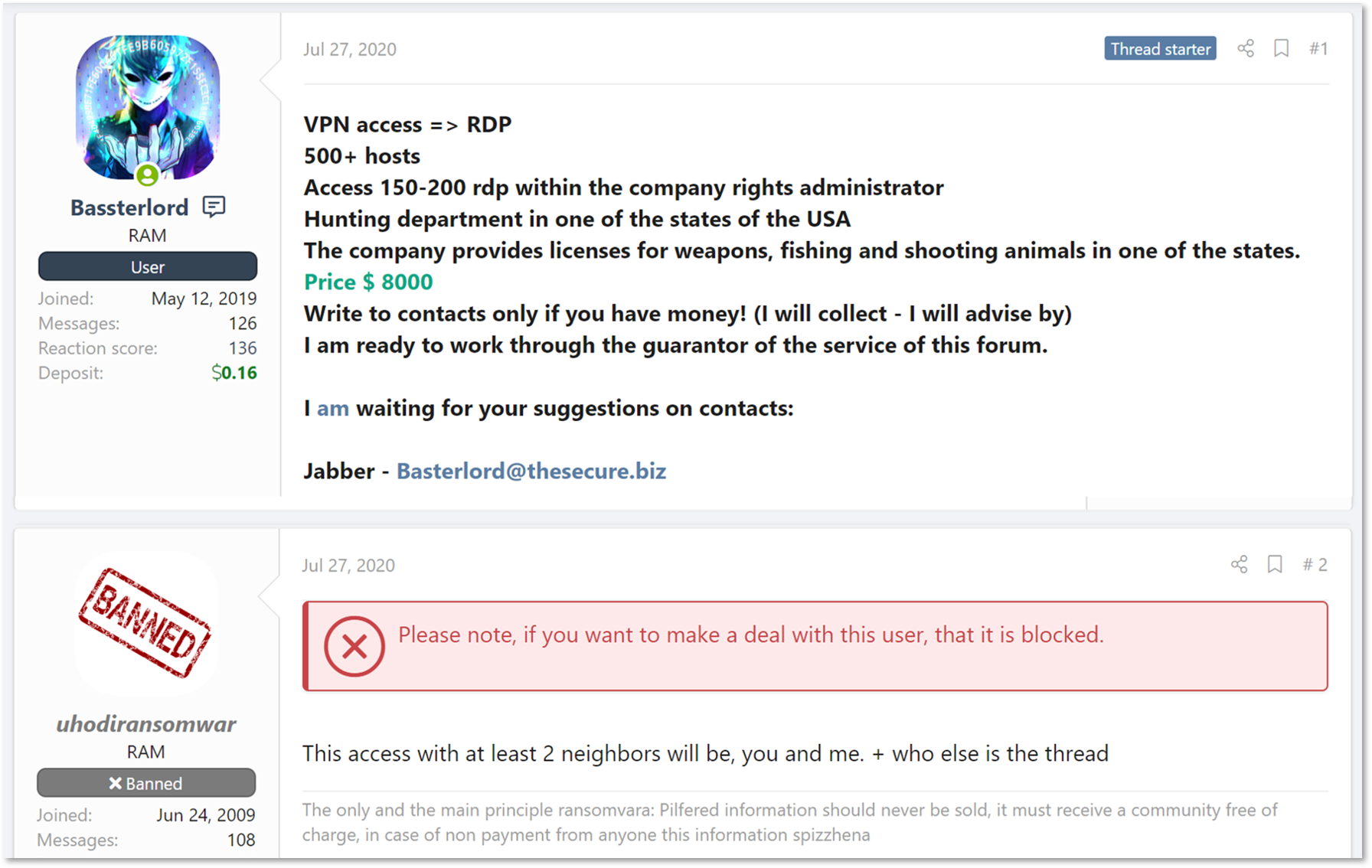

On July 27, 2020, Bassterlord offered network access to a US-based, state-level government organization for USD 8,000. The post claimed that the initial vector was VPN access which then was leveraged into RDP. First responder to the thread was uhodiransomwar, who claimed that the infiltrated network was shared between a few different actors – implying that the backdoor Bassterlord was offering wasn’t exclusive and that he himself has access to the server already, and therefore may be worth less than the price asked.

Google-translated post where Bassterlord recently posted access to a government entity in the US for sale.

The actors continued their public discussion, with Bassterlord admitting that the initial VPN access was indeed public knowledge – implying that multiple actors knew about it to begin with. He later made the case that even though multiple actors may be aware of the access itself, he’s not aware of the inner workings on the network – only to his own access, leveraged into RDP. He also claims that in his eyes, network access – even if shared – should be “first come, first serve”: the first actor to leverage it into a full-blown attack gets the spoils. This exemplifies the role of an initial access broker in the ransomware supply chain: they are the function that can take an initial lead to a vulnerability, and work it into a full blown network access. Thus, several actors working on the same initial access may come up with different results – creating an arms race between brokers and the affiliates who drive them.

This dialogue, though appears to be superficial, showcases that uhodiransomwar was able to identify the victim only through Bassterlord’s description of it – meaning he had actual access to it as well. This fact implies that, somewhere, initial access brokers and affiliates may have access to some shared database of breached entities.

Very quickly this proved to indeed be the case, as on August 3, 2020, uhodiransomwar published the aforementioned Pulse Secure leak. In his main post, the actor claimed to be tired of other actors posing these so-called “public” compromises as private access to corporations and trying to profit off of them – hinting towards Bassterlord’s latest offers.

Bassterlord’s Little Black Book

Upon investigating the content of the leak, KELA was quickly able to match against several network accesses offered by the actor – proving that the leak indeed was the source of multiple (if not all) of Bassterlord’s offers as an initial access broker. Specifically, we were able to trace servers back to the government entity mentioned in the paragraph above – as well as another of Bassterlord’s victims: a university to which he sold access for USD 12,000 on July 12.

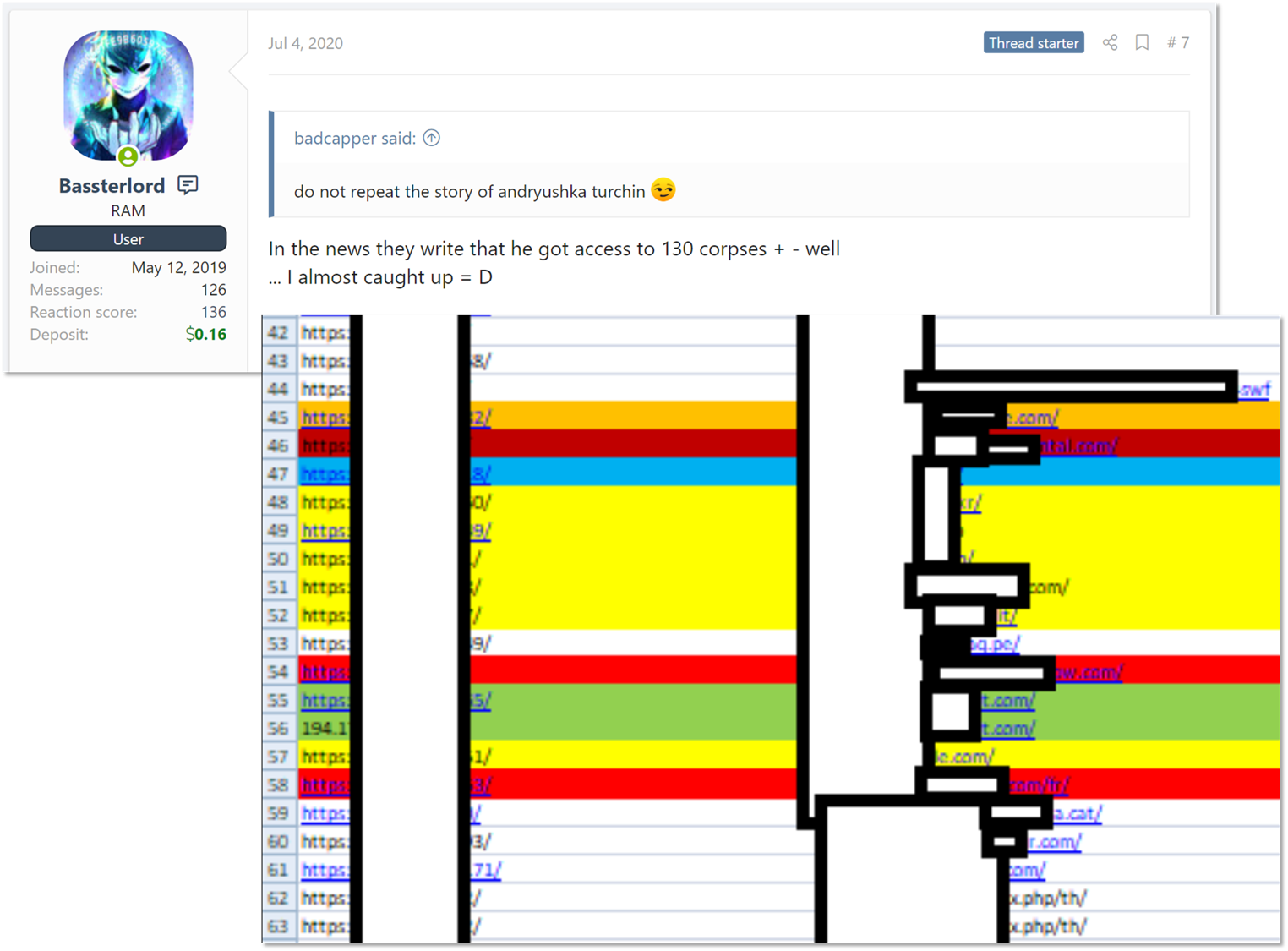

After identifying several victims, we tried to get to the bottom of the list; where did it originate, and was it really passed between actors who were discreetly sharing compromises? Digging a bit back into previous posts by the actor, we found a reference in which Bassterlord stated that he has potential access to at least 77 organizations known to be vulnerable. In this thread, Bassterlord, somewhat braggingly, likened himself to Andrey Turchin – the main figure behind the notorious initial access broker FXMSP – stating that “in the news, they write that he [FXMSP – KELA] got access to more than 130 corporations. So… I’m almost caught up with him”. To this post, Bassterlord attached a heavily redacted screenshot of an Excel file that seems to contain dozens of entries, each one representing an initial entry vector (assumed to be a vulnerable Pulse Secure server) to an organization.

Bassterlord’s post and a snapshot of his access list

The fact that Bassterlord was maintaining an active list of VPN-based accesses, coupled with the fact that uhodiransomwar claimed to have knowledge and access to it, implies that some version of this list was being shared or circulated internally between actors.

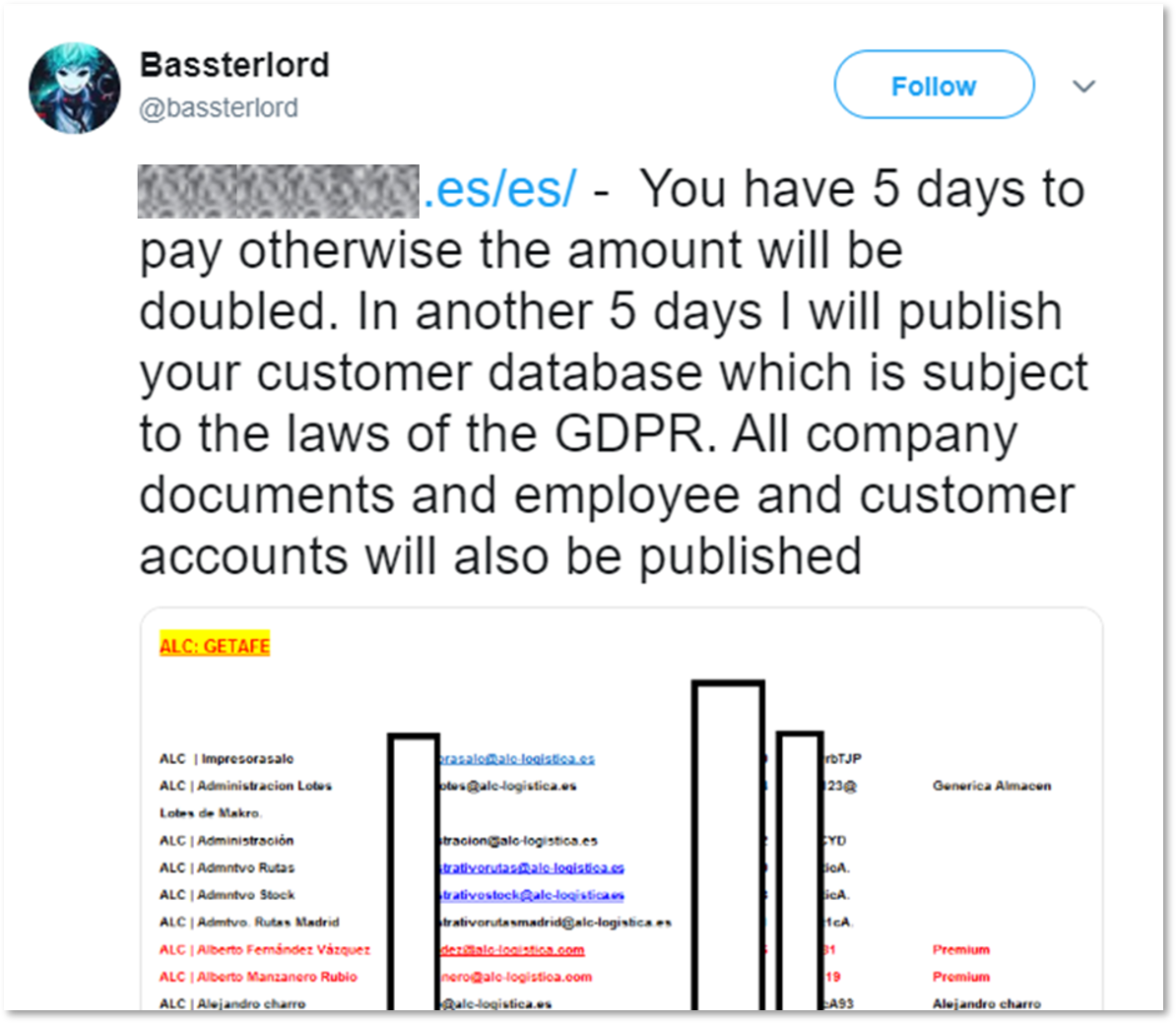

At times it seems that Bassterlord was trying to break out of the initial access broker cage and monetize his network accesses via direct extortion demands. A now-deleted tweet from July 11 by the actor taunts a Spain-based firm to pay within 5 days, or risk GDPR fines. However, it’s unclear whether this claimed attack was carried out via actual ransomware or manual extortion. Another hint to Bassterlord’s attempts to deploy ransomware is his post from July 12, where he discontinued the sale of access to a Thailand media company because it was “locked by me [him] personally”.

What’s in a List?

The full files leaked by uhodiransomwar and covered by ZDNet were in fact an archive, containing over 900 txt files – each pertaining to an exploited Secure Pulse server, and accompanied with notes taken by the actor who compiled the archive.

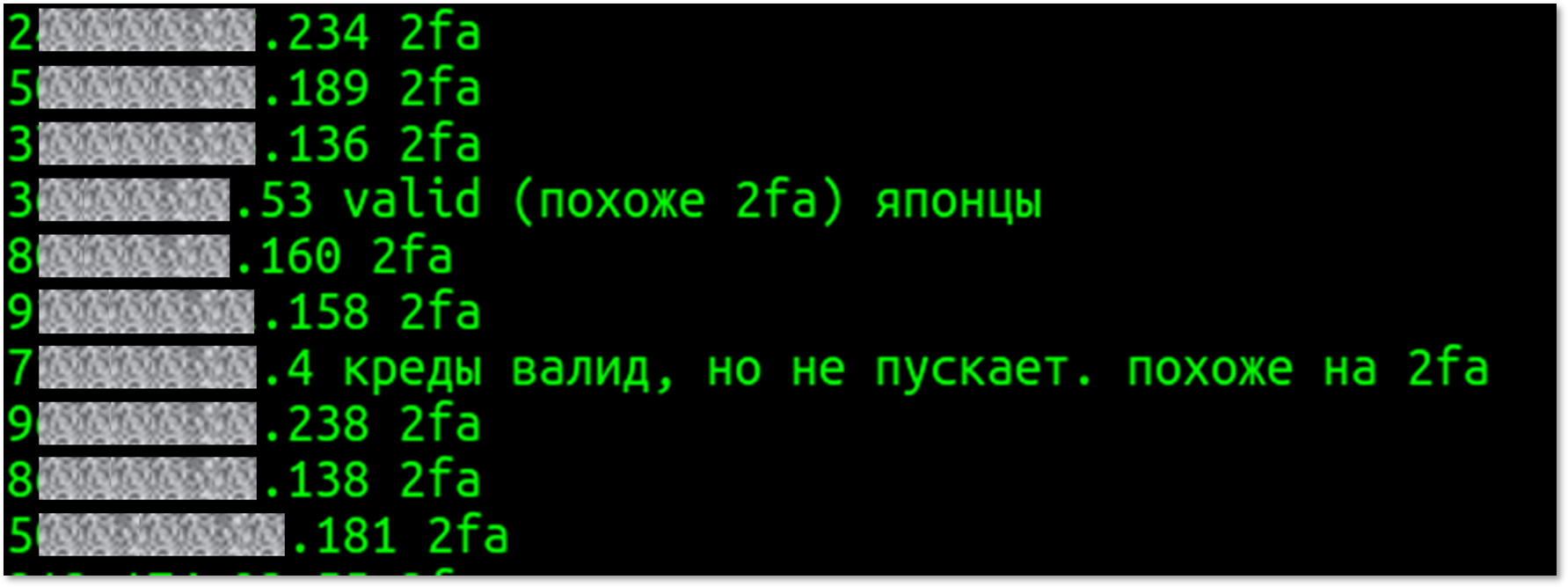

For example, 49 of the 900+ servers are noted to require two factor authentication in order to login to the admin panel:

Raw notes from the leaked archive, mentioning servers with 2FA

Of the remaining servers, around 250 are noted to be “bad”, “invalid” or otherwise inaccessible – and over 150 are noted as “need hash” (probably referring to a lack of a key data point – a password hash or a key – within the data obtained from the server, probably rendering it not as easily accessible).

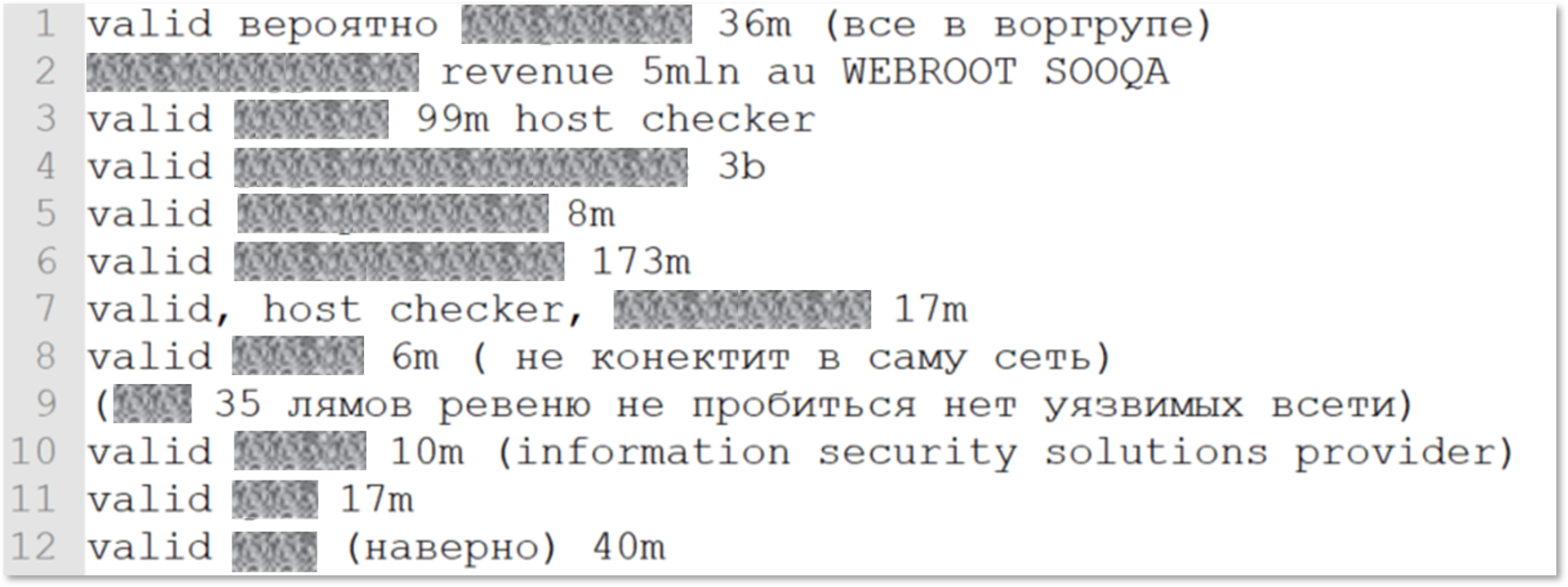

Overall, it seems that around 400 of the servers included in the list are potentially valid and can be leveraged to deploy ransomware. Of these, some have notes mentioning the name of the company and, quite commonly, the organization’s revenue as well:

Notes mentioning potential victims’ revenue in a shortened notation. For example, “17m” (row 7) means USD 17 million, and “3b” means USD 3 billion

Sifting through these notes, one can easily trace several multi-million dollar companies – several of them public – as well as a few with over a billion USD in revenue. These findings showcase the threat level that big, seemingly well-protected organizations may face from relatively novice actors acting as initial access brokers.

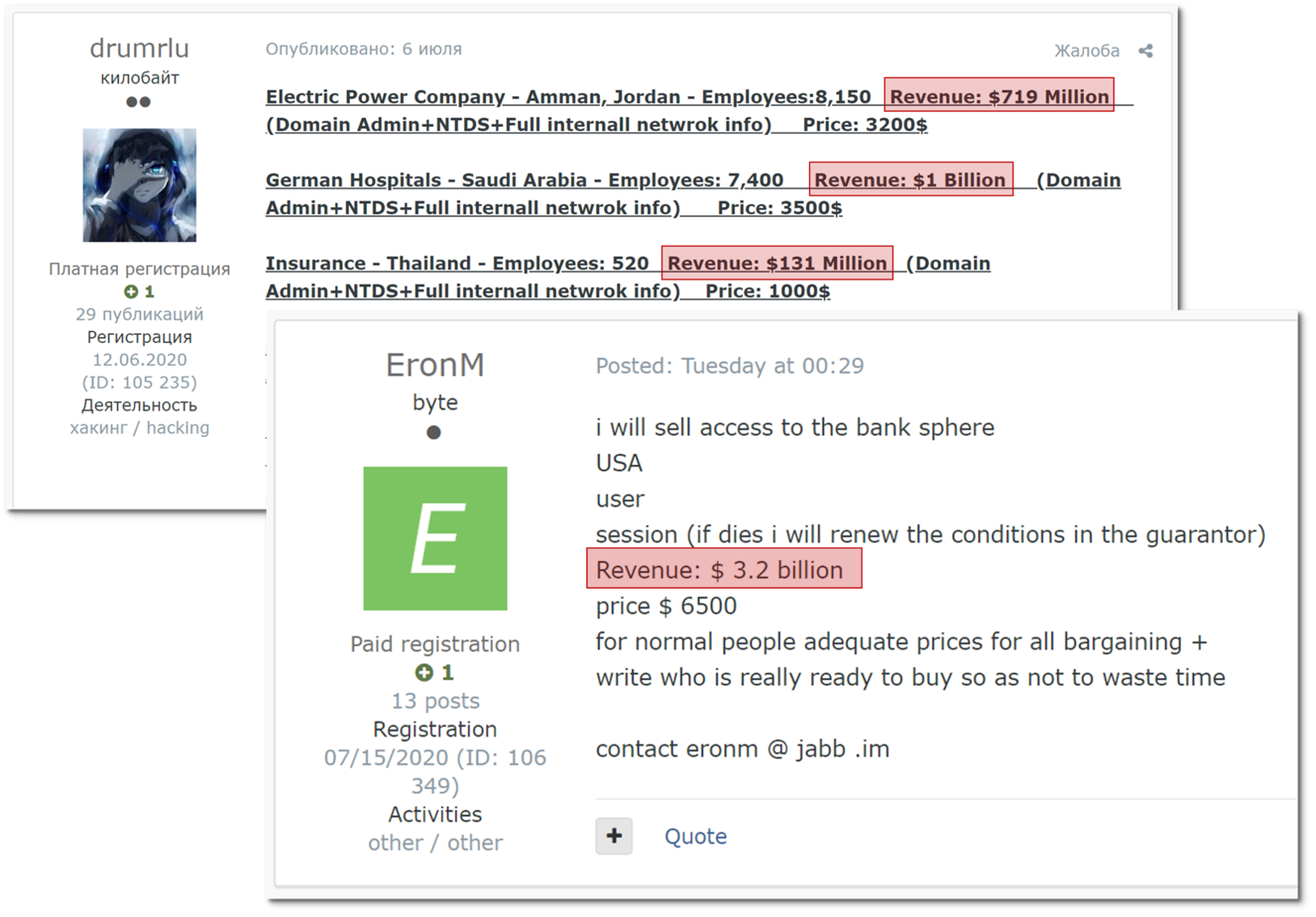

Researching victims’ revenue is a very common practice for initial access brokers, whose posts lately tend to mention revenue of their victims in order to entice potential buyers – based on an assumption that organizations with higher revenues would have the potential for a multi-million dollar ransom.

Sales posts made by initial access brokers noting their victims’ revenues

The real question to try and answer is: How many of the entries in the archive made it past initial access brokers to ransomware affiliates – suffering a full-blown ransomware attack. Here, the main obstacle in finding an answer is the sheer amount of ransomware attacks that go unreported by the victims.

Still, we were able to track leads to several companies that are publicly known to have suffered a breach that were mentioned in the files. For example, the file contains a mention of a company known to have impacted by a naming-and-shaming ransom actor; while we can’t corroborate a direct cause-and-effect relationship here, this leak still serves as a reminder that monitoring cybercrime sources can prove crucial for organizations.